One of my favourite albums is E.S.P. by Miles Davis' second quintet; and one of my favourite songs is Ron Carter's R. J. I was listening to it again, and then decided to listen to it more analytically a few months ago. Depending on what version you listen to, it's really interesting; especially when you compare it to the notation (the only source for this is from the Aebersold book on Ron Carter—but it's a definitive one since Ron Carter himself appears on the play-along). I thus decided to do a comparison between the notation and transcriptions of four recordings, to lead to a different way of notating the song. This isn't to say that the Aebersold notation is "wrong" (because it can't be). As the world's most recorded jazz bassist, the lynch-pin of numerous seminal groups and an educated composer and lecturer, it should not be surprising that a composition by Ron Carter should reveal many possibilities in harmony, rhythm and melody; and it was a fun few hours thinking about those ideas. This may not be an easy read for people not trained in music, but I will give as much help as I can.

I used Sonic Visualiser to aid me in the transcriptions: a nifty program once you get into it. I used MuseScore to notate everything. All errors my own doing.

The music

I'm going to give three options for listening:

- here's a list of available albums on Discogs;

- this is a Spotify playlist; and

- here's a YouTube playlist.

Oh, here's a PDF of my re-notation.

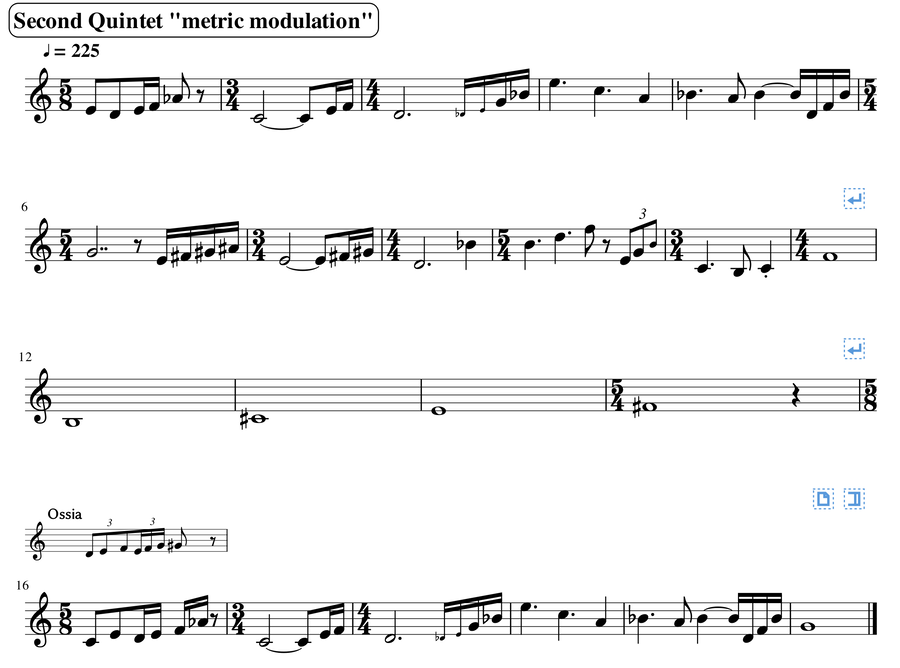

Transcription of the classic version (CV)

I am of course talking about the recording on E.S.P. This is more a performance transcription. Here, Shorter and Carter create tension on the A♭ in the first bar by pausing just before the first beat of the next measure. This sets up the ear to perceive the changes in metre. Williams aids this perception by strongly accenting the longer notes in the phrases. This is the same length as the Aebersold version (80 quavers = 20 measures of 4/4).

The remarkable thing about both recordings by the Second Quintet is the way Shorter, Carter and Williams breathe together. The melody is given a looser feel than the transcription suggests. There are many group compositional effects at play here: Shorter wilfully ignores the instruction — or perhaps it is not there! — to play a G in bar 15, opting for the F♯ both in the studio on E.S.P. (1965), and live at Newport (1966). In combination with Hancock's harmonisations, this produces an aural comma instead of the finality of the G in other versions.

On the studio version, Shorter extemporises the beginning double triplet figure (bars 1 and 16 in the standard notated version below); he's playing the theme, but not quite, and (to my ears) it gives the melody a mischievous quality.

Joe Henderson treats the melody as a cadenza in his version on Tetragon (1968). He transmutes the first figure into a saxophone-oriented rip up to the A♭, and flurries, bobs, and weaves into the stresses of the theme along the way. This radicalisation of the theme is then matched by his solo. In their own ways, Shorter and Henderson make the song a part of their improvisational language, and perhaps this is what I cannot perceive in the later versions.

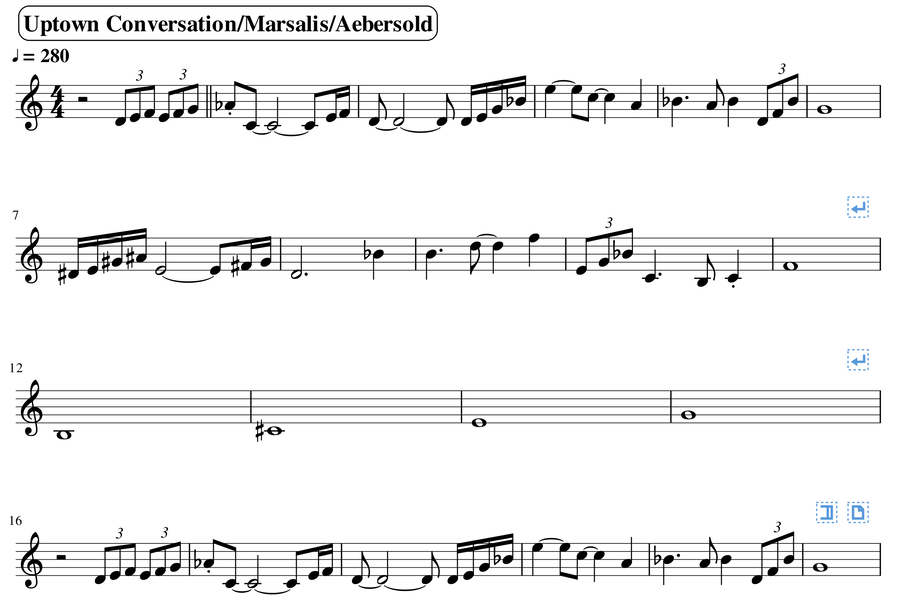

The standard notated version

You can hear this version on Uptown Conversation (1970) and Wynton Marsalis' eponymous album (1982); and this is the notation used in the Aebersold book. The placement of the A♭ as the downbeat in the first bar — only a quaver's difference from the E.S.P. version — is all it takes to push the song into a more rigid territory than the classic version.

The phrase in mm. 7–9 puts the ear in a clear "jazz" field with strong pushes on the 1 and 31 (not shown in the notation, but on each recording these beats are consistently played slightly early). The Marsalis is typically bombastic (later Tony Williams drumming!), and the tempo chosen for the Uptown Conversation version puts it in the same quality of his early work with Dolphy on Where?. But on each of these recordings (which are later than what I shall call the classic version) there is something missing for me; I suspect this is partly down to nostalgia for the version I prefer rather than any judgement on the playing on the records.

Harmony

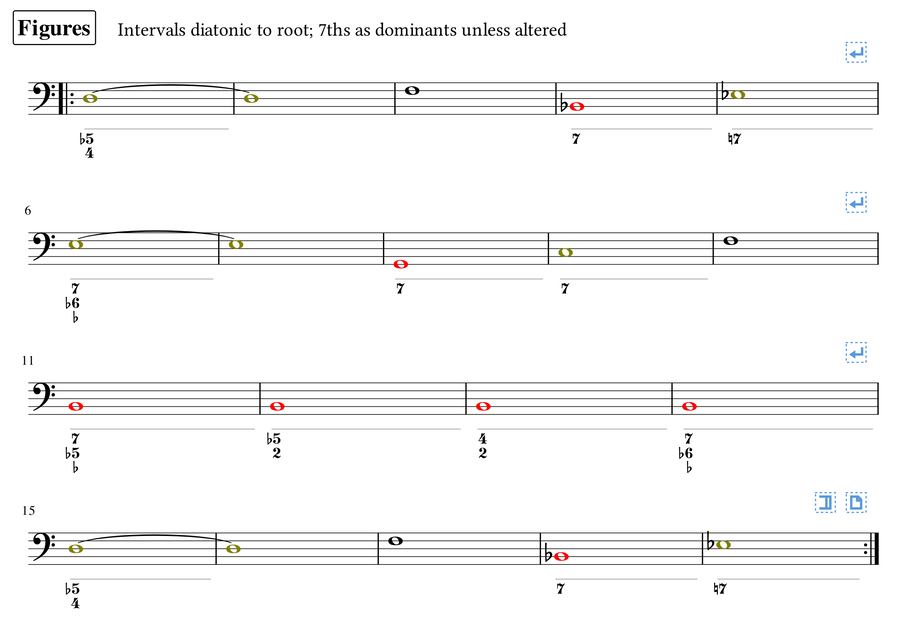

It is important to stress that the nature of how we think of Western harmony has been transformed since the early 20th Century; and jazz practice and performance is crucial to that transformation. So there's no reason why we should limit Carter's thinking of harmony to "melody here, chords here". Working out the harmony is made even more difficult when you have a pianist like Herbie Hancock as well as Carter. Their use of harmony in the Second Quintet was startling; an open, fluid form of tonality that chord symbols don't adequately express. But there is another way to express harmony that is older yet more suitable for improvised music performance: figured bass. Below is a possible interpretation.

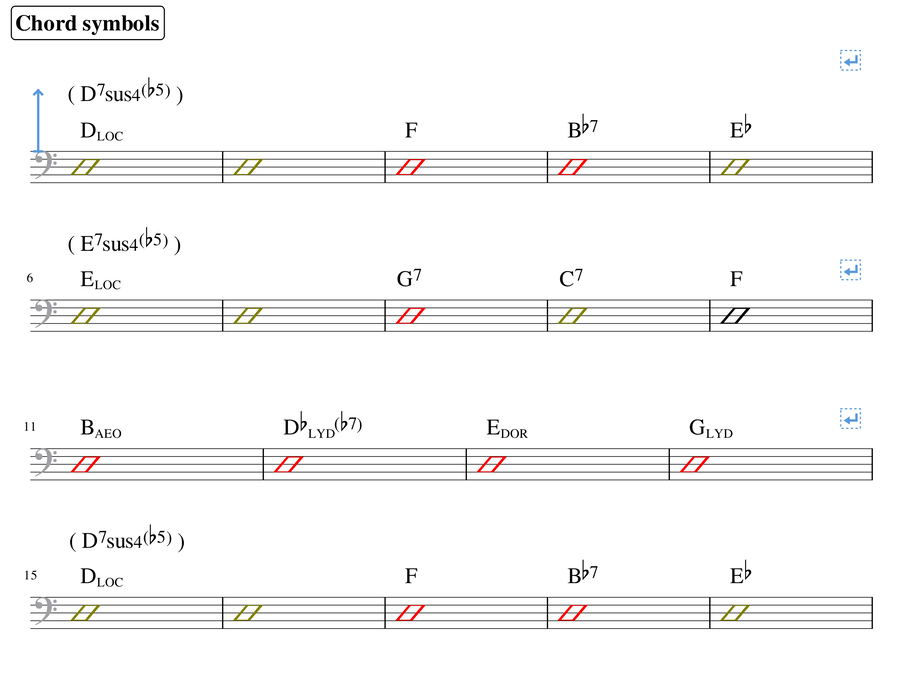

However, in jazz and popular music it's common to produce chord or scale symbols to represent the underlying harmony of a composition, and the method shouldn't be just ignored. So using my style guide, I re-wrote the harmonisations. Looking at the Aebersold score, there's a D∅♯2 chord in the first bar; but this make little sense, as a sharpened second from D is F (E♯). Transcription led me to identify it as a dominant seventh chord on D with a suspended fourth and a flattened fifth (same notes, more logical). Furthermore, if perceived as series of modern modes instead of chords, a more faithful representation of Hancock's (and Don Friedman's) variations can be imagined, as well as allowing for the later versions. This is presented below.

AEO = Aeolian; LOC = Locrian; DOR = Dorian; LYD = Lydian

-

I realise here that someone will say "no, jazz is the two and the four!" but this is over-simplistic, and not reflective of what's happening in the music; there's always a fluid, deliberate movement of accent. ↩

comments (0)

Sign in to comment using almost any profile.